Parties, Actors and Actions

caution

This page has been moved to the eSSIF-Lab Framework on Github.

Summary

This pattern captures the essence of how things are done. It answers questions such as: "Who/what does things?", "How are their actions being guided/controlled?", "Who controls whom/what?", "Who/what may be held accountable?". These questions need to have a precise answer if you want to design or implement systems where actors can be anything, ranging from programs/apps running on computers as well as humans. This pattern provides a way of looking at organizations, people (human beings), and non-human actors. It shows how they interact with one another, and how they may or may not work for one another. The pattern descibes how parties are 'sovereign' as they construct their own world view, reason with that, and make their (sovereign, subjective) decisions. It also shows how this 'knowledge is used, where it is used, and also: where it is not used. The latter implies that parties have a limited scope of control, which gives rise to their need to work together with other parties, that have their own sovereignty. Such interactions with others, however, are outside the scope of this pattern.

Purpose

In order for people or organizations to decide what to do (themselves), what to ask others to do (for which these others generally require some form of compensation, how to know that the associated risks are worth taking, this pattern provides a simple mental model that provides the basis for thinking/reasoning about such questions. The pattern is expected to be helpful to those that think about designing complex systems (systems of systems) that are owned by different parties, and in which both human and non-human actors take part.

Introduction

One may readily observe that in some way, people (humans) and organizations are similar. This is indicated e.g. by the notion of 'personality' that many legal jurisdictions assign to (specific kinds of) organizations. It allows rights and duties to be assigned to people and organizations alike. It also means that people and organizations can be held accountable, and be subjected to prosecution.

The main characteristic that people and organizations share, is that each of them autonomously sets its own (subjective) objectives, maintains its own (subjective) knowledge, and uses that to pursue these objectives. This characteristic qualifies them as parties.

One may also readily observe that in other ways, people and organizations differ. For example, people eat and drink, whereas organizations do not. People can sit behind a computer keyboard, type texts, hit the 'Enter' button, e.g. to send an email. Organizations cannot do that. In short: people can act (do things), and hence qualify as actors. Organizations cannot do things (act) and hence do not qualify as an actor. This is what sets people and organizations apart.

Parties and Actors

Notwithstanding that organizations cannot act, it is quite common to hear statements that seem to imply that they can. If ACME is an organization and someone says: "I just received mail from ACME", this cannot be literally true as organizations cannot send messages. It is either a person or a computer system that has actually sent it. Statements such as these must therefor be interpreted in a figurative way, as a 'shorthand' for 'I just received mail that was sent by some actor that was acting on behalf of ACME'.

When an actor is acting on behalf of some party, we mean to say that it is actually in the process of executing a (single) action, which it executes on that (single) party's behalf. These constraints (a single action and a single party) allow for:

- assigning accountability for the execution of that action to a single party;

- an actor to execute different actions for different parties (i.e.: to multi-task for different parties).

In this relation is acting on behalf of, the actor plays the role of agent (of that party), and the party plays the role of principal (of that actor). Note that for every agent-principle pair, an action must exist that the agent is executing on behalf of its principal.

We also need to talk about actors for which it is realistic that they might do something for some party at some point in time. We will use the term work for for actor-party pairs that qualify. We see two basic ways for such a relationship to exist:

One way is where the party has a legal or rightful title to control (own) the actor.1 This would e.g. be the case if the actor were a computer program (a running mail client or mail server, or an app running on a mobile device). We use the term owns to relate a party with an actor for which this is the case. In this relation owns, the actor plays the role of the owned, and the party plays the role of the owner.

The second way is where an actor works for a party, based e.g. on some kind of agreement or contract. A party can hire an actor that it doesn't own, i.e. create arrangements with other parties that enable the actor to work for that party. How such works for relationships may start or cease to exist, and be modified, is the topic of the pattern mandates, Delegation and Hiring.

Action Execution

Actions are executed in a specific context, i.e. a specific place and time, and a specific party on whose behalf the action is executed. The knowledge of that party provides the policy, i.e. the rules, working-instructions, preferences and other guidance that the actor needs to execute the action. For example, sending a mail on behalf of some organization may require that the mail template and logo of that organization be used. Or accepting an order usually requires a check to see the order is 'clean', i.e. can be processed by others in the organization. What a 'clean-order check' comprises is part of the knowledge of that organization.The policies that govern the execution of an action are part of the knowledge of the party on whose behalf the action is being executed. As a concequence, an actor that executes the action must be able to access (the knowledge that) the policy (is part of). Also, the actor must use that policy as its primary guidance for executing the action.

Note that this does not imply that the actor cannot use knowledge from other sources (parties) as well. In particular, human actors are typically responsible (not necessarily accountable) for their doings and may hence use their own knowledge. They may also look for complementary, third party knowledge, e.g. on the Internet or in a library. However, using the principal's knowledge as the primary guidance is important if that principal is to be held accountable.

Realizing Objectives

Every party has its own mission (calling, vocation), and realizing that is often perceived as the reason for its existence (raison d'etre). This is what drives them. It causes the party to set its (other, derived) objectives, and determine how to realize them, e.g. by finding (and subsequently owning, or employing) actors that can do the associated work, by establishing and maintaining the policies for the actions they will be tasked to execute, etc.

Setting objectives, managing the associated risks (i.e. 'effect of uncertainty on objectives'), deciding about laws/regulations to comply with, etc., is the topic of Governance, Risk Management and Compliance (GRC), which is outside the scope of this model.

Formalized model

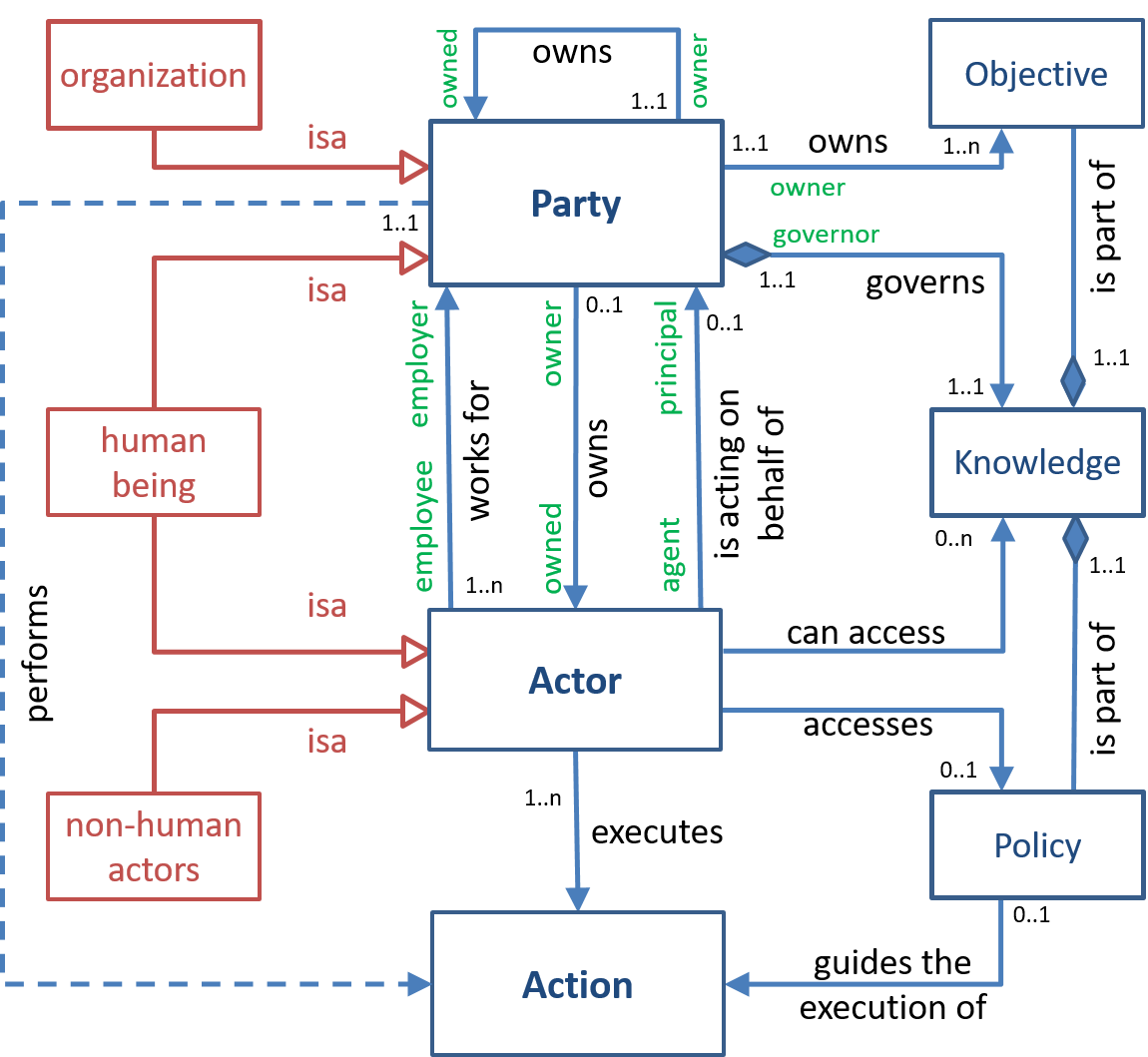

Here is a visual representation of this pattern, using the following notations and conventions:

It shows that parties (humans, organizations) perform actions for the purpose of realizing their objectives. Parties are not considered to actually execute such actions; they have (human and non-human) actors that work for them, execute such actions, using the party's knowledge as the (authoritative) guidance for executing the actions (as well as any other relevant knowledge they can access).

The essential characteristic of parties is their 1-1 link with knowledge, which they continually update and use e.g. for reasoning, decision making, and determining e.g. what to do, when, and with whom. Knowledge not only includes (observable) facts, but also opinions, e.g. regarding the entities it knows to exist, relations between them, and rules (constraints, logic2) that can be used to classify and reasoning about them, and for making decisions.

Perhaps the most important idea in this pattern is that our party concept is not considered to (be able to) act, and they need actors (i.e. Entities that can act) to act on their behalf and thus make them perform. This does, however, not preclude having entities that are both party and actor - e.g. humans - and that such entities can act on their 'own' behalf. And we can continue to use the commonly used form of speech in which a party performs some Action by realizing that this means that there is (at least) one actor that is actually executing that action.

In this pattern, knowledge takes center stage. Knowledge contains objectives to be realized and managed. This not only triggers all sorts of actions to be performed, but also guides their execution in terms of when an Action should start, when it terminates, which actors qualify for executing it, etc. Everything that is specific for a party is reflected in its knowledge.

This works well for human beings, which are both a party and an actor. So a human being can act, implying itself as an actor, and using its personal knowledge as guidance. The model also works when a human being (as a party) may hire someone else (as an actor), e.g. to fill in his tax return form. This other is guided by the knowledge of the human being that hired him, and uses its own knowledge for the details of filling in the tax form.

It also works well for organizations, which are typically companies, enterprises, governments or parts thereof, i.e. groups of human beings and possibly other actors that, as a group, fit the criteria for being a party. This group of actors would typically work to realize the organization's objectives, being guided by the organization's knowledge (registrations, policies, etc.). Like human beings, an organization may (have an appropriate actor) decide to hire or fire actors for longer or shorter periods.

Parties set objectives that they seek to achieve, the most basic of which perhaps is its mission, or its 'raison d'être', to the realization of which all of its actions are (ultimately) aimed. Every Objective is owned by a single party (we do not consider 'shared objectives'[^3]).Footnotes

- Noting that this also covers slavery merely serves as proof that the model is very generic, not that we support slavery.↩

- I.e. “logic is the analysis and appraisal of arguments (Gensler, Harry J. (2017) [2002]. "Chapter 1: Introduction". Introduction to logic (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 1. doi:10.4324/9781315693361. ISBN 9781138910591. OCLC 957680480.)↩